|

|

|

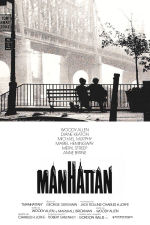

Manhattan

(1979)

|

Directed

by:

Woody Allen |

COUNTRY

USA |

|

GENRE

Drama/Comedy |

|

NORWEGIAN TITLE

Manhattan |

|

RUNNING

TIME

96 minutes |

|

|

Produced

by:

Charles H. Joffe |

|

Written by:

Woody Allen

Marshall

Brickman |

Review

Woody Allen's perhaps most outright

love letter to New York City, and his first movie in black-and-white,

is a small-scale comedy/drama with a hint of grandeur in the cinematography

department and the use of George Gershwin's music. Woody plays

Isaac Davis, a 42-year-old writer who just can't seem to find

the right one. His latest ex-wife, played by Meryl Streep,

seems to be inherited from Dustin Hoffman in

Kramer vs. Kramer. And

his most recent conquest is a 17-year-old high school student (Mariel

Hemingway), a relationship he justifies by constantly referring to

her as "too young". Then he meets culture connoisseur Mary (Diane Keaton), and everything seems to click into place. Although, we all know that

nothing ever really does with Woody Allen. And this is of course the

basis for the bittersweet symmetry which has always given his movies a certain

slice-of-life veracity. For that to be true for Manhattan,

however, you'll have to buy into the fantasy that this odd-looking,

bespectacled, middle-aged little man can be the object of attraction

for a

beautiful, modern 17-year-old. But hey, this was the 1970s, and in

retrospect, it is fair to say that Allen with this subnarrative

tapped into a zeitgeist which existed in the wake of the sexual revolution

– arguably

more than what he was aware of himself at the time. There is an undeniable appeal in

watching these fundamentally unjudgmental characters interact – it

vividly illustrates how much the world has changed since 1979,

arguably for both better and worse. But the movie and Isaac's many

relationships and fiddlings with love aren't just a reflection of

the times, they are also a reflection of Woody's hubris. And herein

lies the reason why Manhattan doesn't quite work as the grandiose romantic comedy

Allen set out to make, because running through its down-to-earth

snobbery is a slight but constantly discernible indulgence. A

certainty about its own cleverness and importance which not only

impairs Woody's sometimes brilliant observations and phraseology,

but also makes you aware of the story's inherent mediocrity.

|

|